Mini organs, big breakthroughs: Scaling organoids for next-generation drug discovery

Experts explore the technologies and innovations transforming organoids into scalable platforms for drug discovery

12 Feb 2026

Organoids are self-assembling 'mini organs' driving a new era in personalized medicine and next-generation therapies. These 3D models more closely reflect human biology than traditional 2D cultures or animal systems, changing how we study disease and develop drugs.

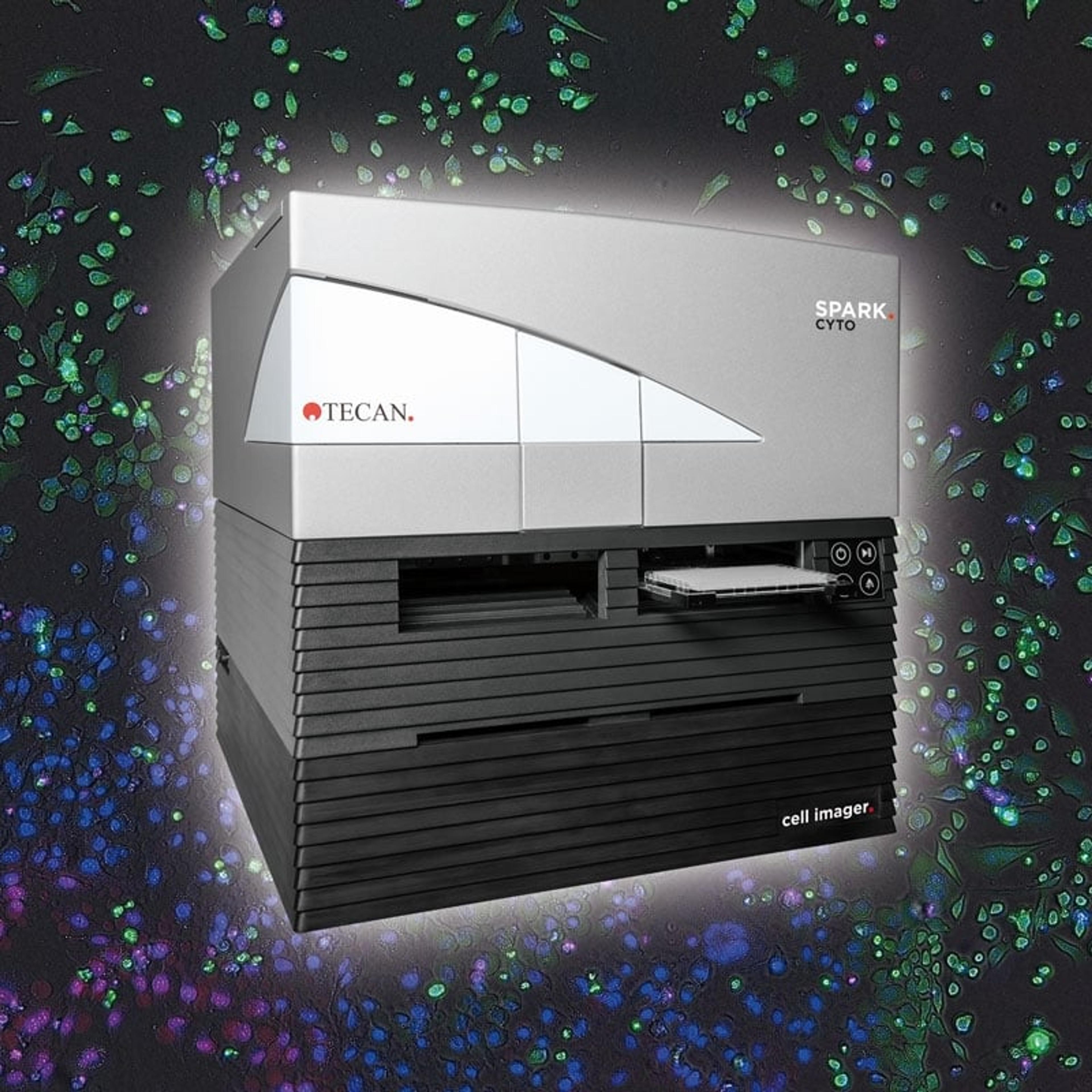

In this SelectScience® Forum, held in partnership with Tecan, experts discuss how to transition these powerful 3D models from the lab bench into industrialized, high-throughput screening environments to truly deliver the next generation of drug discovery.

The panel included Dr. Thomas Hartung of Johns Hopkins University, Dr. John McLean of Vanderbilt University, and Dr. Simone Sidoli of Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

From animal models to 3D human organoids

Organoid research has advanced rapidly over the past two decades. When Dr. Hartung began working with 3D rat brain organoids in the early 2000s, robust methods for modeling human tissue were still limited, and many early systems relied on animal-derived models.

“The breakthrough came with the availability of induced pluripotent stem cells, which allowed us to humanize our models,” he explained. “By 2013, we were among the first groups to develop human brain organoids, and by 2016, we had achieved the first mass-produced, standardized brain organoids.”

“This solved a fundamental problem,” he said. “We cannot ethically experiment directly on human brains, but these technologies now allow us to study aspects of the brain that are only possible in 3D systems.”

For Dr. Sidoli, who first started working in organoids when he launched his lab around seven years ago, the transformation has been visible even within this relatively short timeframe. “The technology has matured to the point where growing organoids is no longer as technically challenging as it once was,” he said, “shifting them from niche expertise to systems that many labs can now realistically adopt.”

3D models are transforming modern drug discovery

A core theme of the discussion was the growing inadequacy of traditional 2D cell cultures and animal models for modern drug discovery. “More than one-third of new drugs are biologicals designed to modulate complex pathways,” said Dr. Hartung. “Traditional 2D cultures and animal models often can’t capture the complex mechanisms that determine how these therapies actually behave in humans. Therefore, to more effectively assess the efficacy and safety of new drugs, we need models that better reflect human biology.”

“This is why organoids are so valuable. By recreating aspects of human tissue structure and function in 3D, they allow researchers to study drug responses in a setting that more closely resembles the patient,” he said.

Dr. Sidoli echoed this view, offering a specific example from his work on aging. “A critical aspect of aging is the misfolding and disorganization of DNA,” he explained. “But traditional 2D cultures consist of cells that are constantly proliferating, which is counterproductive when studying DNA structure and macromolecular organization. In adult tissues such as the brain, many cells divide rarely, if at all.”

“By preserving more realistic tissue architecture and cellular behavior, organoids provide a model that more closely reflects how human tissues function in vivo,” he said. This is critical in aging research, where subtle cellular changes drive disease and influence how therapies work.

Barriers to implementing organoid systems

Despite their growing importance, implementing organoid systems still faces several hurdles. “One of the main challenges is time,” said Dr. Sidoli. “Organoids take longer to grow than traditional cell cultures because they need time to assemble, establish cellular connections, and reach a physiologically relevant state.”

Dr. McLean described reproducibility as a hurdle in his early work with organ-on-chip systems. “One of the main challenges was ensuring device-to-device consistency and system-wide control,” he said. “Linking multiple organ systems made this even more complex, and establishing a shared culture environment that preserved function across systems took years to refine.”

Dr. Sidoli added that because organoids better reflect real human tissue, they are naturally more complex to analyze. “Organoids are inherently heterogeneous. But that’s precisely what makes them valuable because real organs are heterogeneous. With the right technology, we can overcome this challenge and better understand this complexity.”

The technologies powering next-generation organoid research

As organoids grow more complex, ensuring consistent results and quality depends on more sophisticated analytical tools. In his organ-on-chip systems, Dr. McLean’s team uses ion mobility–mass spectrometry to monitor what tissues secrete in real time and how these change in response to drugs or environmental stressors. “Unlike traditional liquid chromatography, ion mobility operates on the millisecond timescale,” he explained, “allowing rapid separation and structural characterization of highly complex molecular mixtures.”

“Our goal is to build comprehensive molecular catalogs that capture how the whole organoid system responds to a drug, creating datasets that can then be analyzed using machine learning to uncover meaningful patterns,” he added.

Dr. Hartung emphasized the importance of multiomics in interpreting organoid systems: “Looking at a single readout is rarely enough to understand what is happening in complex organoids,” he said. “By combining different layers of data, such as transcriptomics and metabolomics, we can see whether the same biological pathway is affected at multiple levels. When independent datasets point to the same pathway, it strengthens confidence that the effect is real and biologically meaningful.”

He and Dr. Sidoli added that making sense of these large, layered datasets increasingly relies on artificial intelligence (AI). Modern experiments can measure thousands of genes, proteins, and cellular features simultaneously, generating multidimensional datasets that are simply too complex for humans to fully grasp.

Scaling organoids for industrial drug discovery

Looking ahead, the panel agreed that moving organoids into routine drug discovery will require not only technical refinement, but also smarter integration of automation, analytics, and biological insight.

Dr. McLean identified two priorities: reducing cost to enable larger-scale experimentation, and advancing high-resolution approaches such as single-cell analyses to preserve biological depth. “Scaling must go hand in hand with confidence in the data,” he said.

Dr. Sidoli highlighted single-cell technologies and AI-driven image analysis as key to scaling organoid systems. “Resolving differences at the cellular level will be essential to improving our understanding of disease,” he said.

To translate that biological depth into scalable workflows, he emphasized the importance of automation and continuous imaging. “If we can use AI to interpret morphological changes in real time, we may not always need complex molecular assays to assess drug response,” he explained. He added that making organoids easier to produce and transport would further reduce technical barriers and broaden industrial adoption.

Dr. Hartung agreed that AI will underpin the field’s next phase. “To turn data into real biological insight, we need powerful computational tools that can spot patterns and make sense of it.” He also emphasized the importance of quality assurance and reporting standards, including Good In Vitro Reporting Standards, to ensure reproducibility and enable reliable AI-driven analysis.

“Improving functional maturity and immunocompetence in organoids will also be essential for modeling the inflammatory components present in most human diseases,” he added.

Realizing the full potential of organoid technologies

In closing, the panel explained that progress not only depends on the technology itself but also on the people behind it. “Education is key,” said Dr. Hartung. “Organoid systems have advanced enormously over the past 15 years, but they’re still not fully embedded in biomedical training. There are far too many people who aren’t aware of the opportunity here and are sticking to methodologies that are outdated. We need stronger formal education and continuing training, especially as regulatory agencies are increasingly recognizing the value of human-relevant systems.”

“Science is made by people,” added Dr. Sidoli. “Organoids can seem complex, but there are systems that are very feasible to set up in a lab, and there’s a community of scientists excited to train others. If we want this field to move forward, we need to make it accessible and bring more people into it.”

Dr. McLean agreed that training must evolve alongside the science. “This field sits at the intersection of chemistry, biology, engineering, and data science,” he said. “If we equip researchers to work across disciplines, we’ll be in a much stronger position to translate organoid innovation into real-world impact.”