Atomic-scale imaging breaks speed barriers in Glasgow lab

Researchers harness next-generation detectors to capture magnetic dynamics in microseconds

26 Jan 2026

The Materials and Condensed Matter Physics Group at the University of Glasgow, part of the School of Physics and Astronomy, has a long history in the development and application of ion and electron microscopy techniques. The team has particular expertise in quantitative Lorentz methods for imaging magnetic materials, electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) and diffraction methods.

Their research spans a wide range of material systems, including: thermoelectrics, energy materials (barocalorics), topological insulators, optical coatings for gravitational wave interferometers, high-strength steels, magnetic racetrack memory, magnetic nanoparticles, magnetic multilayers and non-collinear antiferromagnetic systems.

Areas of focus include synthetic antiferromagnetic multilayer systems, in particular using four-dimensional scanning transmission electron microscopy (4D-STEM) differential phase contrast (DPC) to examine the magnetic textures in these materials. Other areas include designing and characterizing beam-sensitive barocaloric molecular crystals and investigating magnetic skyrmion dynamics.

The Materials and Condensed Matter Physics Group at the University of Glasgow

Time-resolved magnetic dynamics in focus

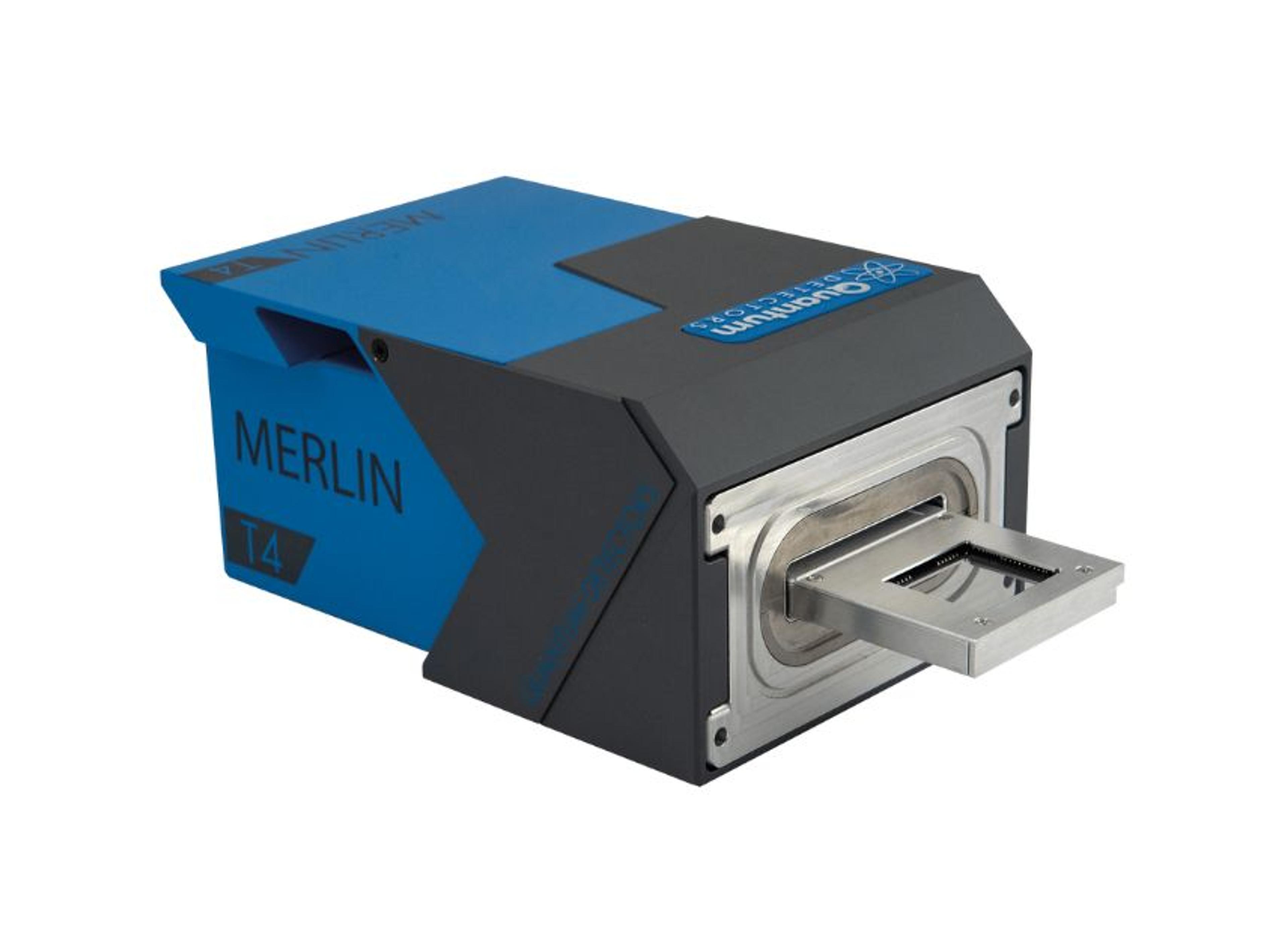

Matúš Krajňák, Application Scientist at Quantum Detectors, has been working with the Materials and Condensed Matter Physics Group to use electron microscopy to explore time-resolved magnetic dynamics in materials like FeGe imaging systems, such as SrTiO₃. This work has relied on the Merlin T4, a next-generation hybrid pixel detector built on CERN's Timepix4 chip. The Merlin T4 has both ultrafast fill-frame readout and event-based acquisition capabilities.

“Our motivation stems from both scientific interest and technical benchmarking. My colleague Fred Rendell-Bhatti, Lecturer and Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Glasgow, spent some time researching skyrmion dynamics in FeGe, where he observed rich and complex magnetic dynamics involving the deformation and spontaneous creation and annihilation of skyrmions. His findings led us to identify FeGe as an ideal candidate material for ultrafast imaging,” explains Krajňák. “We saw an opportunity to use the capabilities of the Merlin T4 hybrid pixel detector to help us to explore these dynamics further, and potentially uncover new physical phenomena associated with the interplay between energetical stability and topological charge conservation.”

As a next step, the team at the University of Glasgow selected SrTiO₃ as a model system for benchmarking performance of the detector for 4D-STEM imaging experiments.

“The well-characterized structure of SrTiO₃ made it ideal for benchmarking. By using the event-based STEM detection mode, we were able to push the scan speed to the limit of our scan engine and still obtain virtual ADF images with clearly resolved atomic columns as a first step for other 4D-STEM experiments,” said Krajňák.

Expanding research using a next-generation detector

Previous studies involving imaging of fast (sub-ms) dynamic processes of magnetic skyrmions used the Merlin detector, but this limited the team to approximately 800 µs frame times. Switching to the Merlin T4 to image the same system improved time-resolution by a factor of more than thirty.

“This change provided us with significant opportunities to capture previously inaccessible mechanistic details associated with complex skyrmion dynamics,” said Krajňák. “The integration of the hardware was simple and only took the Quantum Detectors engineers a couple of days. The workflow associated with the Merlin T4 was similar enough to the Merlin, such that the learning curve was not too steep in moving from one system to another.”

The Merlin T4 could be integrated into the existing JEOL ARM200cf atomic resolution analytical electron microscope without replacing the entire Merlin system, and this allowed the team to carry out comparative studies by imaging the same samples sequentially with both systems.

According to Krajňák, the Merlin T4 has allowed the team to advance its research: “Most experiments with the next-generation detector don’t need to consider detector time-resolution as a limiting factor. This means that optimizations elsewhere, such as samples or imaging conditions, will lead to an increase in detectability. This is an exciting prospect, for example with beam-sensitive energy materials, where many short, multi-frame acquisitions can result in microstructural insight without destroying the sample.

Researchers imaging skyrmion dynamics in frame-based mode, where frames are sparse, have to optimize beam-conditions for maximum brightness. The team used PCA (principal component analysis) denoising to extract the signal associated with key configurational skyrmion states. The PCA STEM analysis used HyperSpy, an open-source Python framework for exploring, visualizing and analyzing multi-dimensional data.

“Interestingly we have found that even with relatively sparse frames – around two electrons per pixel – the microsecond resolution imaging or the Merlin T4 meant that we were able to reconstruct skyrmion lattice reconfiguration occurring on timescales of tens of microseconds, where the spatial resolution scales with the number of frames in the input dataset,” said Krajňák.

The role of event-based and multi-frame acquisition modes

The team have used the Merlin T4’s event-based and multi-frame acquisition modes to image SrTiO to help them to understand how quickly they could acquire a 4D-STEM dataset. They believe that the technique could be useful for looking at beam-sensitive materials. Event-based imaging methods increase data density by removing the requirement to store information in sparse frames. This improves the data efficiency of image acquisition.

“The multi-framing approach has the benefit of drift correction, which is applicable to all types of imaging. We can use this in cases that necessitate a longer total dwell time. These cases were previously impractical because of the speed of the previous generation of direct electron detectors,” said Krajňák.

Processing and analyzing the data

According to Krajňák, the high speed and availability of both frame and event-based modes makes the Merlin T4 an impressive detector. However, this brings the challenge of managing the extraordinary amounts of data it produces. Krajňák is working with the researchers to find the best approach to working with the data from the Merlin T4 detector.

“I have written base scripts in Python to support the analysis of the event-based 4D-STEM data. These can be used to adapt existing methods and explore new methods for data analysis,” said Krajňák. “We are also developing a series of Python scripts using Jupyter Notebook for processing and analysis, and these will be shared between group members.”

What’s next for ultrafast electron imaging?

As a next step, the Materials and Condensed Matter Physics Group is looking forward to using Merlin T4 with its new Iliad scanning electron microscope, due to be installed early 2026.

“This will expand the use of the microscope and detector and will be particularly exciting for investigations of momentum-resolved EELS,” said Krajňák. “The Iliad combined with the T4 will be better suited to studying beam-sensitive energy materials, one of Fred Rendell-Bhatti’s research focuses, and the team is excited to investigate the as-yet unachieved atomic scale imaging of barocaloric molecular crystals.”

Overall, the team at the University of Glasgow believes that the ultra-bright source of the Iliad microscope, combined with the Merlin T4 detector, will enable them to access more information from phenomena across the width and breadth of Materials and Condensed Matter Physics Group’s research areas.