What to look for in a flow cytometer: We ask a technical specialist and a cancer researcher

Two flow cytometry experts share the new capabilities and diverse applications of the technology for deeper biological insights

17 Jan 2022

Considered a fundamental technology in cell-based research, flow cytometry is often used in broad biological research projects. With the technical support offered by core facilities, researchers can design insightful experiments to examine cells on a deeper level than ever before. As such, when choosing a flow cytometer, its technical performance and application range become equally important parameters.

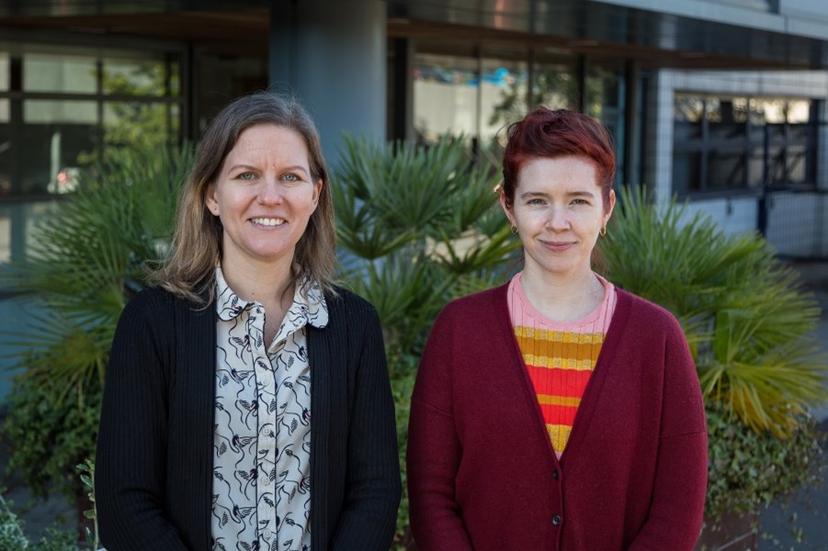

In this SelectScience® article, we speak with two experts from the MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine (MRC WIMM), a research institute under the University of Oxford, about what they each look for when working with flow cytometers.

Flow cytometry: An essential technology for biological research

At the flow cytometry core facility, the eight analyzers and five cell sorters serve more than 50 research groups, staying busy all year long. “We have about 200 regular users over a year,” says Sally-Ann Clark, one of the institute’s flow cytometry specialists. “Our users’ research projects are rather diverse, spanning topics such as hematology, immunology, oncology, and neuroscience.”

With years of expertise in flow cytometry protocols, Clark recalls how the technology has evolved significantly over the past 20 years. “When I first started using flow cytometry, it was on a two-laser, four-parameter analyzer. It allowed us to perform the basic three- or four-color immunophenotyping,” she notes. “Now, we have instruments in our facility which are capable of measuring up to 30 parameters.”

“As there are several laboratories in the building with overlapping research interests, it helps to have flow cytometers that have broad application,” says Jennifer O’Sullivan, a clinical hematologist and DPhil student who uses the core facility. “Whether someone is isolating single stem cells or performing bulk sorting on a larger proportion of cells, given the number of different users, the flow cytometer must be applicable across several projects.”

Looking at both sides: Technical capabilities vs. application possibilities

Even in the era of powerful flow cytometers, the types of flow cytometry users typically fall into two broad categories. “On one end are users interested in looking at only one, two, or at most three colors because they're simply interested in getting a yes/no answer,” says Clark. “Typically, for these applications, the user wants to know if the cells express a certain protein or not and want fast answers on a relatively limited budget”.

“On the other end of the spectrum are users interested in sorting their cells into different cell types and then phenotyping them. These typically involve complex panels and require multiparameter instruments to achieve a better resolution,” explains Clark.

“As a researcher dealing with human samples that are very rare, it can be quite challenging to process these samples within a specific timeframe,” adds O’Sullivan. “Being able to operate independently on an easy-to-use, versatile flow cytometer is key.”

O’Sullivan works in Prof. Adam Mead's group at the MRC WIMM, where the team focuses on studying the pathophysiology of a specific type of blood cancer called myeloproliferative neoplasm. “I'm particularly looking at why some of these blood cancers develop into a more advanced stage. For this, I use flow cytometry to examine a rare group of stem cells in the bone marrow that acquires a genetic mutation. This cell group comprises ~1% of all cells, so they’re a very rare subtype,” says O’Sullivan.

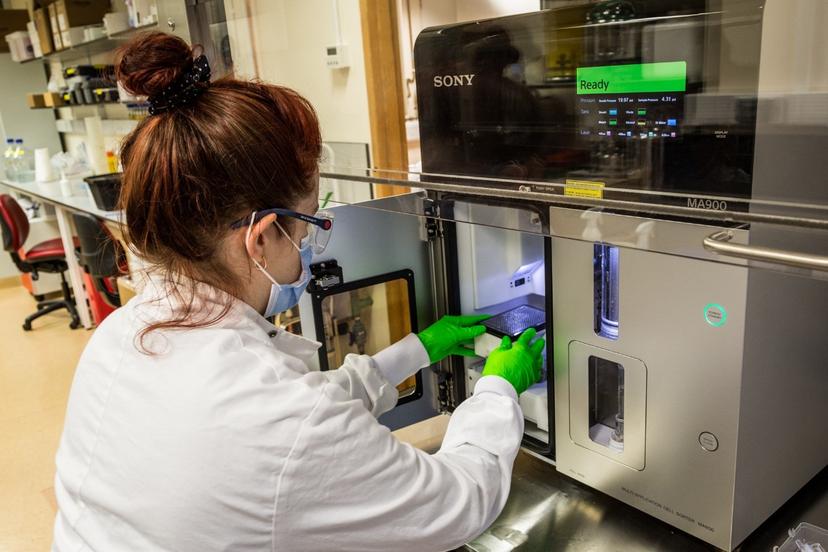

“For my project, I’m trying to isolate these rare bone marrow stem cells,” shares O’Sullivan, providing her perspective from the application side. “The MA900 cell sorter allows me to isolate these cells and sort them into individual wells of a 384-well plate so I can subsequently analyze each cell. As the system is user-friendly, I’m able to operate the instrument from start to finish without requiring any assistance from the facility managers.”

The attributes of an effective flow cytometer

Precision: In analyzing rare stem cells, O’Sullivan’s protocol requires the cells to be positioned precisely in 384-well plates. “The Sony MA900 cell sorting system allows me to detect these cells and then isolate them very precisely within the wells, which are both necessary steps to subsequently process the material,” she says. “The system allows me to perform frequent checks on the plate positions. Agility is crucial for these samples as the material needs to be processed quite quickly.”

Easy to train: As a specialist who needs to train users on flow cytometry, Clark explains how being able to operate the system with confidence, even when core facility staff members aren’t available, gives researchers the independence to work to a schedule convenient for them: “Because it's a relatively user-friendly and easy-to-use sorter, we can train people to use it independently with much more success than some other cell sorters that can be technologically demanding.”

Easy troubleshooting: “The system guides the user through troubleshooting,” says O’Sullivan. “This means, for the most part, the user can resolve potential issues without requiring technical support.” Clark agrees that the troubleshooting is very simple on this system: “It has on-screen troubleshooting wizards that take users through potential issues they might be experiencing. If there’s a technical problem, it can be identified relatively quickly and resolved, even if one isn’t a flow cytometry specialist.”

Reliable and hands-off: “If your routine experiments require bulk sorting of cells, once the system is switched on and calibrated at the beginning of the day, users can reliably load hundreds of millions of cells in tubes and set it for sorting with relatively little monitoring,” notes Clark.

Flow cytometry is here to stay

Technological advancements in the industry have introduced novel cell analysis techniques such as mass cytometry, imaging cytometry or single-cell sequencing. However, many of them are either expensive, require a steep learning curve, demand cumbersome data processing, or simply can’t provide answers as quickly as flow cytometry can.

According to Clark, flow cytometry is here to stay. “Flow cytometry has undergone its own advancement in the recent past, with better lasers, detectors, and spectral analyzers being developed,” she says. “These enable us to perform 30-parameter flow cytometry to phenotype cells on the same level as mass cytometry.” Even when employing advanced methods such as mass cytometry or single-cell sequencing, flow cytometry will remain a reliable method of choice for validating hypotheses before taking projects to the next level.

As for O’Sullivan’s research plans, she says: “I see myself continuing to use flow cytometry as the research takes on a more clinically relevant angle to find new targets for patient groups with limited treatment options.”