How organ-on-a-chip technology delivers human-relevant results

CN Bio shares why organ-on-a-chip technology outperforms traditional 2D cell cultures and animal models

13 Jan 2026

Dr. Kostrzewski has more than 15 years of experience in molecular and cellular biology research and has been Chief Scientific Officer of CN Bio since 2023.

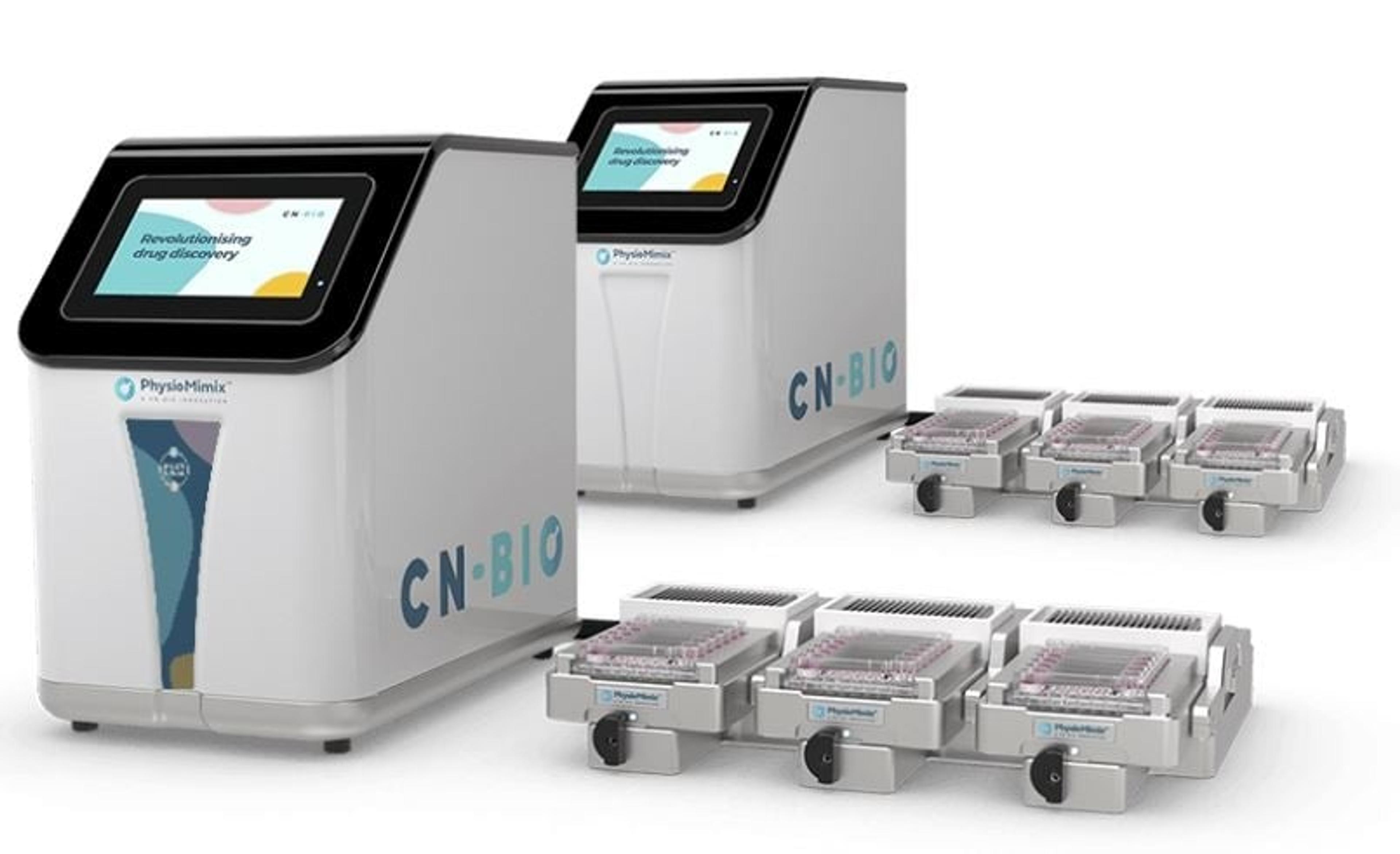

Drug discovery has long relied on 2D cell culture models and animal testing, but these traditional approaches face critical limitations in predicting human drug responses. Flat, static in vitro cell cultures fail to replicate the complexity of human biology, while animal models often produce misleading results due to species-specific differences in metabolism and physiology. Enter organ-on-a-chip (OOC) technology, also known as microphysiological systems (MPS) – a breakthrough that creates dynamic, perfused 3D tissue models to deliver more human-relevant data. By mimicking organ-level functions and enabling multi-organ connectivity, OOC platforms are transforming drug development, toxicology, and disease modeling, paving the way for new approach methodologies (NAMs) endorsed by regulatory bodies. In this SelectScience interview, Dr. Thomas Kostrzewski, Chief Scientific Officer at CN Bio shares his expert insight.

Find the latest 3D cell culture news in our Accelerating Science Feature exploring how scientists are uncovering the mechanisms behind disease and driving breakthroughs in treatment.

Visit resourceWhat are the limitations of traditional 2D cell culture and animal models that organ-on-a-chip (OOC) technology is designed to solve?

Traditionally, the equipment, workflows, and methods used for drug discovery testing are optimized for simple static 2-dimensional cell cultures on flat microplate surfaces, but human biology is not flat, simple, nor static. Whilst 2D cultures are convenient and scalable, they are limited in their ability to predict more complex and latent drug responses or deliver mechanistic insights into modes of action. Typical 2D in vitro cell cultures assess a single phenotypic readout rather than more holistically assessing how cells respond to interaction with a drug.

For nearly a century, animal testing has been at the cornerstone of drug development, however, its limitations are stark. Billions are invested into drug discovery annually, yet most drugs never reach the market because inherent species differences cause inaccurate predictions of drug responses in humans. For example, rodents have a fundamentally different metabolic profile to humans and express a wide range of different key metabolic enzymes. This problem is becoming exacerbated by the influx of new drug modalities which rely on human-specific modes of action for which animal testing is even less suited, often with human-specific drug targets not even found to be present in animal tissues.

Organ-on-a-chip (OOC) technology, also known as microphysiological systems (MPS), generates 3-dimensional organ and tissue mimics that are perfused by fluidic flow to recreate the bloodstream. These lab-grown mimics have been demonstrated to function and respond to drugs in a more human predictive manner, plus they can be linked together to simulate processes such as drug absorption and metabolism to more accurately predict a drugs bioavailability, or to understand interactions between organs, such as inflammation, which drive disease and cause unexpected toxicities.

What key physiological function does the dynamic, perfused environment of your platform provide that static 3D organoids cannot?

There is more than one key function that the dynamic perfused environment of OOC provides that static 3D organoids cannot. The most important include culture longevity (up to 4 weeks for OOC enabling investigations into prolonged chronic exposure to drugs alongside long-term studies of more complex biological interactions), immune-component inclusion, sensitivity and linking organs together into multi-organ systems.

Whilst it is possible to use 3D organoids in advanced cell culture studies, they cannot replicate the human-relevant physiological relevance, or spatial organization of tissues in the same way as OOC, particularly for barrier organs such as the lungs, where the apical side is subject to the air when breathing.

Consequently, organoids have limited use for study areas including infection, environmental research, and drug development, as the main route of entry into the lung – aerosolization and inhalation – cannot occur. Furthermore, key pulmonary functional endpoints such as cilia beat frequency and mucus production cannot be fully assessed. Utilizing OOC, researchers can create more physiologically relevant barrier models enabling simultaneous epithelial exposure to the air and media perfusion underneath1,2.

Regarding sensitivity, an interesting study by Nitsche et al., explored the potential of liver assays of varied configurations including 2D and perfused organoid culture to model cholestatic chemical effects3. Their findings highlighted that Bile acid synthesis was detectable but of low magnitude in organoid culture, however, the cultures failed to replicate cholestatic injury biomarkers when test compounds were applied. By comparison, primary human hepatocyte liver-on-a-chip microtissues responded to all three test compounds reporting decreased bile acid release, a biomarker of cholestatic injury.

Another key limitation of organoids, immunocompetence, can also be circumvented by incorporating tissue-resident and peripheral immune cells into OOC models, the latter of which are circulated by media perfusion. The recapitulation of the immune system allows scientists to uncover immune-mediated toxicity issues, induce common disorders that have an inflammatory element, such as metabolic dysfunction-associated liver disease (MASH) or to model human responses to infection, where animal use is less suited.

Which specific disease or toxicity model has demonstrated the greatest improvement in human predictability using your OOC system?

There are two areas of high demand that we see, one is modelling metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). Human metabolic disorders in general are complex, multifactorial and challenging to study. In the past, researchers had to choose between animal models, which do not adequately reflect human liver metabolism, and simple cell cultures that lack the complexity of a real organ or tissue. In 2023, our MASH model supported the characterization of a novel drug candidate, leading to the initiation of a Phase 1 clinical trial for Inipharm’s INI-822. This milestone marks the first instance of OOC data supporting the clinical progression of a drug for a highly prevalent and complex metabolic liver disease for which there are limited treatment options.

The other area that is emerging is modeling the lung and lung disease. It is a well-known fact that respiratory diseases are the second leading cause of death globally and that current treatments are purely supportive. Over the last 40 years, very few novel therapeutics have been delivered caused by a lack of reliable in vitro and in vivo animal models for research and development. Traditional in vitro models offer limited physiological relevance and animal models differ in anatomy, immune and inflammatory response to humans.

How does the capability to link multiple organs on your platform fundamentally change the study of drug absorption and metabolism (ADME)?

Traditionally, in vitro absorption and permeability data is generated using Caco-2 models, in combination with in vitro liver clearance assays using suspension hepatocytes. This approach fails to account for the pharmacokinetics of a drug after it is absorbed and metabolized by the gut to estimate what proportion actually reaches the liver. Therefore, the use of isolated assays leaves a significant gap in our knowledge when estimating a drug’s bioavailability.

Our PhysioMimix multi-organ Gut/Liver model uniquely allows for intestinal absorption and hepatic clearance to be studied in a single, interconnected fully primary human tissue system. Therefore, by complementing Caco-2 studies with our approach, you obtain an understanding of the combined effects of the human gut and liver to more accurately profile oral drug bioavailability in vitro. Furthermore, Caco-2 cell models are less suited when working with pro-drugs due to their expression of carboxylesterase 1 & 2 (CES1 and CES2) expression, which does not reflect the expression of these key enzymes in the human intestine.

With the growing legislative and ethical pressure to phase out animal testing, how is OOC technology positioned as a viable and human-relevant new approach methodology (NAM)?

OOC technology is not just an ethical alternative, it is a regulatory-endorsed approach with research demonstrating its scientific superiority in supporting efforts to bridge the translational gap in drug development. While challenges remain around validation, standardization and data sharing to fully remove adoption barriers, the combination of legislative support, FDA qualification programs, industry validation studies and integration with in silico tools positions OOC as a critical enabler of the NAM revolution

To what extent are regulatory bodies currently accepting OOC data, and how is CN Bio contributing to the standardization needed for wider industry adoption?

CN Bio has been, and remains, actively involved in numerous consortia, groups, and networks that are driving change to facilitate broader adoption of MPS within our industry. These include direct and indirect work with agencies such as FNIH, ICCVAM, and C-PATH, who work with the FDA to facilitate interagency coordination and accelerate the process by pooling expertise, data, and resources across the US government and other relevant agencies.

One example is an ongoing project led by the 3Rs Collaborative (3RsC). This effort brings together regulators, technology providers, end-users, and non-profits to advance the responsible use of MPS in regulatory applications.

In partnership with 3RsC, the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), 9 commercial providers, 1 end-user, NIH-NICEATM, and C-Path, we are embarking on a project to evaluate the use of Liver MPS to detect Drug-induced liver injury (DILI). The goal is to assess variability across multiple platforms using the same experimental protocol, to enhance confidence in the accuracy, reliability, and standardized characterization of these models. The results of this study will be published in early 2026.

In the current research landscape, why is peer-to-peer communication in science so important?

Peer-to-peer communication is critical for furthering science because it accelerates trust, knowledge transfer, and collaborative problem-solving. Within the field of OOC, the pace of regulatory change has gained so much momentum this year that keeping pace is starting to feel like a shared mission! Although it’s now a question of when, rather than if animal testing will eventually be replaced, social proof is required to support those that remain skeptical to take the next step. Shared case studies and validation data demonstrate reliability, and reproducibility will help to build regulatory confidence, accelerate standardization and best practices, whilst cross discipline collaboration across engineering, biology and computational modeling will enable faster innovation cycles.

References

Phan et al., Advanced pathophysiology mimicking lung models for accelerated drug discovery, Biomat Res. 2023.

Caygill et al., Dynamic Culture Improves the Predictive Power of Bronchial and Alveolar Airway Models of SARS-CoV-2 Infection bioRxiv, 2025.

Nitsche et al., Exploring the potential of liver microphysiological systems of varied configurations to model cholestatic chemical effects. Arch Toxicol (2025).